© Negar Sadeghian,

Charles III University of Madrid (Spain)

Twenty-three years: from 1910 to 1933. That was the period that marked the beginning and the end of the first feminism activity in Iran. From the first journal of women, Danesh; until the dissolution of the last feminist association by the government of Pahlavi I: the movement of women’s rights has continued covertly between censorship and criticism.. Those were the years that began with the emergence of the first journal of women, Danesh; until the dissolution of the last feminist association by the government of Pahlavi I, to lead the movement for the rights of women in a covert to escape censorship and critical level.

Iranian women have been at the center of social and political changes and challenges before, during and after the Islamic revolution in 1979. In recent years, however, the new generation of Iranian women is negotiating the notions of “femininity”, sexuality and modernity with the core of power in Iranian society. Along with this negotiation, Iranian cinema, as the screen of the visual reflection of Iranian culture and society, has recently represented an unprecedented representation of women on the big screen. This study approaches the works of some of the important women filmmakers of Iranian cinema like Milani, Derakhshande, Banietemad and some others who after the revolution, decided to make films more related to women’s rights creating the new “New Iranian Cinema” as a paradigm of a new national identity.

Feminism in Iran: a brief history:

In Iran, the term feminism first emerged shortly after the Iranian constitutional revolution in 1910, when the first Danesh women’s newspaper was published and written by women for the first time, although the first women’s rights groups had begun to emerge a few years earlier. With the coming to power of Pahlavi I in 1925, many of the demands for equality became part of his campaign to modernize Iran and win the affection of the people[1], but the women’s rights movement lasted until 1933, when the last association was dissolved by the same government, until the arrival of Pahlavi II in 1941, in the 1950s, women’s rights organizations began to openly advocate for equal political and personal rights.

With Ayatollah Khomeini’s 1979 revolution, the process of advancing women’s rights was interrupted. The legal age of marriage was restored to nine. Women were barred from serving as judges, refused to initiate divorce proceedings, prohibited from serving in the army as well as from participating in sports activities, and the use of the veil for work outside the home was imposed. They also were later banned from participating in sports activities. [2]

Voices of alarm and resistance arose against these actions by the new government, but the activists were identified and labelled as anti-revolutionary and later made to lose their jobs. During the presidency of the reformist Mohammad Khatami (1997 – 2005), a greater female disposition towards women’s rights activities appeared, as the reforms that Khatami represented, had at their core a space to improve women’s rights.[3] Despite all the illusion of a new openness, the more conservative part of the regime continued unrelenting repression against women activists. The repression increased during the first government of Ahmadinejad when activists were regularly harassed, interrogated, arrested and imprisoned.[4] Now with Rohani in office after eight years of conservative executive power, there is apparent new ground for feminist activities. It is paradoxical that even with all these restrictions on feminist activists in Iran, Iranian women enjoy more freedoms than most women in the Middle East. While Iranian women can drive freely, in some countries in the area driving is a dream. There are cases where the right to vote for women did not come until 2012, while Iranian women have been able to exercise it since 1963.[5]

Women’s rights and the new “New Iranian Cinema” as a paradigm for a new national identity

Over the past three decades, of all the paradoxes cultivated in Iranian society, none is more complex than the issues of gender and its representation. A range of aesthetic languages and semantic representations are involved in the cinema to reflect the encounter of the Iranian population with modernity. As a general rule, female representation becomes an effective instrument for the Islamic Republic to generate a process of reproduction of a new national culture. Every social and cultural transformation within Iranian society, especially with regard to women, has inspired the cinema. In recent years, the new generation of Iranian women is negotiating the notions of “femininity”, sexuality and modernity with the core of power in Iranian society. Alongside this negotiation, Iranian cinema has recently exposed an unprecedented representation of women on the big screen. This interpretation is derived from a gender consciousness that is transgressing the boundaries of segregation and inequality. Women filmmakers are entering the realm of representation to bring to the screen stories seen and starred by women themselves.

It was pre-revolutionary: the representation of women reified in the cinema

Before the revolution, the regime of Pahlavi II exercised total control over cultural and artistic production through a censorship committee, which established specific codes for all locally produced films, and thus the Iranian commercial and popular cinema or Filmfarsi[6]was born, characterized by being vulgar and very sexual. The entertainment policy of Pahlavi II distorted social realities. A very evident example of this distortion is the role of women in these films. Roles far from the reality of millions of “ordinary” women. Women in this cinema played two roles: good women and bad women. The good woman “housewife”, without any function beyond the confines of the home; versus the bad woman, destroyer of families influenced by the West, who dresses provocatively, drinks, smokes and dances, disrespecting traditional morality. This was the rule with the exception of a new wave of filmmakers who, away from this stream of commercial films, began to use cinema as a social critic. [7]

A poster for Seven Cities of Love, directed by Hamid Mojtahedi

Post-revolutionary era: from revolution to a “New Cinema”

When the 1979 revolution broke out, observers and industry professionals were concerned about the future of cinema in Iran due to such events as movie theatres being burned down in the name of morality and independent culture, actors and producers being exiled, etc. However, Iranian cinema started to develop more activity. Films produced before the new regime had to be retouched to adapt to the new rules and this meant Islamizing cinema.[8] In order to do this, the regime built a film industry with professionals more likely to comply with its values and political agenda. During this period, “love and women” disappeared. All the premises of the pre-revolutionary regime as well as the production of “vulgar filmmakers” were put as the responsibility of women, ignoring the fact that they had been the main victims.[9] In the development of the revolution, Iranian women were politically active, with an important role in the establishment of the Islamic Republic. However, after the revolution, they were socially marginalized. The regime, aware of the strong presence of women, tried to use tools in order to stop this emergence, and cinema was one of them.

The lack of improvement in relation to the pre-revolutionary era was reflected in the disappointment of spectators and a large number of actors who opted for exile. In response, it was decided to eliminate vulgarity with strict regulations that, among other things, required the use of the Islamic hijab[10] and the prohibition of makeup, close-ups, physical contact with men, or words or signs that could be related to sexual behavior. Although the codes were initially closely followed, some directors who were close to the neo-realist style found alternative ways of adapting their works and ignoring the controls.

Between 1982 and 1992, the former minister and later president Mohammad Khatami laid the foundations for the growth of a national cinema in parallel with a certain freedom of the press, favouring the production of films under a series of reforms, such as the creation of The Farabi Film Foundation to finance films.[11]

Alberto Elena includes in a “New Iranian Cinema” all the new directors that emerged from the 1980s and especially after the Khatami reforms: “a new generation of young filmmakers [who] burst onto the Iranian film scene, supporting those names that are established in the renewal of local cinema and its growing international success.[12] This new panorama provoked the incorporation of women, in front of and behind the cameras as producers and directors of films: Rajshan Bani-Etemad, Puran Derakhshandeh Tahmineh Milani, among others; initiating a process of social transformation in Iran, where cinema offers a place for the artistic representation of new practices of gender and sexuality. Films where a critical vision of women’s daily reality is offered: the mandatory use of the chador[13], the freedom of men to take several wives, the prohibition to travel alone, the impossibility to stay in a hotel if they travel alone, the prohibition to smoke in public, etc. Representations (reflections) of reality and the consequences that social injustices produce.

The use of narrative and visual elements, related to women and accepted globally to act locally, gives a perspective of Glocalization (globalization and localization),[14] within an Iranian cinema that has been opening and closing borders with the outside world. In the absence of a free press, cinema ended up being the vector of social criticism in Iran. The favourable reception given to Iranian cinema by the critics allowed it to be recognised beyond its borders. Cinema became a medium for social criticism and educational work. At the same time, Iranian cinema in the 1990s became the fashionable film industry at international festivals. In 1998, the Iranian film industry ranked tenth in the world in terms of production, surpassing Germany, Brazil, South Korea, Canada and Australia, and well above other production companies in the Middle East, Egypt and Turkey.[15].

In this circumstance, films starring women were made. Although there was a clear difference in the female role in one film and another: while some films by women directors had a clear feminist tendency, there were films in which the representation of women did not overcome the old stereotypes. Therefore, there is a period in which feminism is going to find a place within the Iranian national cinema, in different productions generating strong repercussions (positive and negative) and successes (national and international).

Women in Post-Revolutionary Cinema

In the case of cinema, in parallel with new male directors, women filmmakers – with one or more feature films in their portfolio – in the 1990s exceeded the number of female filmmakers in the previous eight decades of Iranian film history. The number is considered an achievement and is significant in some ways as a result of the cultural resistance of Iranian society against theocratic power and the dominant patriarchal forces that have always looked with suspicion at cinema in general and women in film in particular. According to Naficy, the presentation of women behind and in front of the cameras is divided into three phases: “Absence, pale presence, and powerful presence.”

– The first phase occurs in the early 1980s, when women without veils are shown on the screens, and they have to be painted in black with a marker on the film’s photographic negative.

– The second phase starts in the middle of the 80’s, when the women on the films are almost invisible and always appear in a domestic environment.

– The third phase is in the late 80s, when there is a more visible presentation of women in front of and behind the cameras.

In the first two phases, women were invisible because the filmmakers were self-censoring to avoid possible government censorship when showing women on the screens. Women and men could not look each other in the eye, and the objective and desirous look at women that existed in pre-revolutionary cinema became totally devoid of sexuality. In the third phase the exploration of love began, something that in the other two phases was totally hidden.[16]

Today, despite all the restrictions of the last two decades, there are a considerable number of film school graduates in Iran, among whom are a remarkable number of women making their first films. “Growing presence of women in Iranian cinema is another paradox. In the last two decades, there has been a higher percentage of women directors in Iran than in most countries in the West. The presence of women in the film industry as filmmakers and producers has encouraged many Iranian women, whatever their social status, to leave their destiny in their own hands and fight for their rights, either through film or in some other artistic activity”.[17]

Pouran Derakhshandeh was the first woman director after the 1979 revolution, and although Derakhshandeh made several documentaries before the revolution, her first fiction film was in 1986, The Relationship (Rabete). Derakshandeh in her first film shows a world unknown in Iranian cinema. The director tries to find a solution to the communication problems of disabled children in families and society.[18] in 2013 she directed her film Hush! Girls Don’t Scream (His! Dojtartha faryad nemizanand). This film, which has been the focus of critical attention, is a clear example of female representation that speaks of harassment and sexual abuse of girls.

Another director is Pioneer Rakhshandeh (Rkhashan) Bani Etemad. In her three successful films Narges 1992, The Blue Veil (Roosari Abi, 1994) and The May Lady (Banu-ye Ordibehesht, 1998), starring female characters, she speaks about the situation of women in society without magnifying their prejudices in the patriarchal society. Bani Etemad is more interested in the universal struggle of the lowest rungs of society, regardless of gender. Milos Stehlik, in an interview with Bani Etemad, mentions that “Her films, while predominantly featuring strong female leads are not to be confused with having feminist undertones. Bani Etemad is more interested in the universal struggle of the lower rungs of society, regardless of gender.”[19]

The third pioneering director is Tahmineh Milani. She wrote the script for her first feature film, Children of Divorce (Bacheha-ye talagh in 1989. It is a melodrama about the female condition in a patriarchal society where women are portrayed as victims of male violence. The women in this film suffer psychological and physical damage from the men who are part of their lives: fathers, husbands or even their own children. A turning point in her career was the film Two Women (Do Zan, 1999), the first film of her Fereshteh Trilogy, an unquestionable example of the representation of women in the patriarchal society and the injustices of the established laws.

There are many others like Samira Makhmalbaf who is also a young and important director who in the late 90’s marked her importance. At the age of seventeen, she directed her first feature film The Apple, (Sib, 1998) and became the youngest director in the world to participate in the official section of the 1998 Cannes Film Festival. Although the director is not considered a feminist director or one who represents women by making a difference between the genders, in her first film she speaks of a totally patriarchal society and culture. Makhmalbaf became a member of the Cannes jury at the age of twenty. Another of her films that also speaks about gender injustices is At Five in the Afternoon (Pange asr, 2003). It talks about Afghanistan and the situation of women in the Taliban regime. Although Makhmalbaf’s films have not been successful within the country, they have always been in the spotlight at international festivals. Samira Makhmalbaf is considered one of the most influential directors of the Iranian New Wave. Although directores like Makhmalbaf and others with just one film like Tahmineh Ardakani, Yasaman Malek Nasr ecc, were not successful in Iranian cinemas, they still have an important impact on women’s cinema in Iran after the revolution.

Starting in the year 2000, women’s cinema began a new phase by introducing new women directors every year. Today there are more than thirty women directors who present a new film every year. Although not all of them present films about women in society, most of them try to mention this issue and the diversity of the genre in a direct or indirect way.

Conclusion

Iranian society, like many other societies, is still struggling for gender equality, so visual representations of gender and sexuality – of which cinema occupies an important space – appear to be important steps forward. It is not surprising that in Iran cinema, like any other cultural product, is related to politics. A range of aesthetic expressions and a variety of representations have been reflected in film as the image of the Iranian population’s encounter with modernity. The remarkable fact of this new “new cinema” is undoubtedly the participation of women. Women are joining the film industry, both directing films and playing different stage roles. Not only new actresses appear, but also new directors, producers, technicians and specialists from different phases of the industry. The films directed by women deal with themes that aim to show a daily and critical reality that clashes with the post-revolutionary national imaginary. Feminism is going to find a place within this cinema with different productions and receptions, generating strong positive and negative repercussions and national and international successes.

1. “Silencing the Women’s Rights Movement in Iran, Iran Human Rights Documentation Center”, Iran Human Rights Documentation Center(IHRDC) 2010, pàg.1. [back to the text]

2. IHRDC, op.cit, pág.6

3. Janet Afary, Sexual politics in modern Iran, Cambridge University Press, 2009 [back to the text]

4. IHRDC, op.cit, pág.34. [back to the text]

5. Caitlin Pendleton, Olivia Zhu, “New Feminism in Iran”, Harvard political review, 2011. [back to the text]

6. The Filmfarsi (commercial and popular cinema from before the Revolution) mostly presented women as a mere sexual object and very dependent on men. After the revolution, the Shiite religious considered the “naked” women of Filmfarsi as an element of corruption of the youth. Véase. Hamid Naficy, op. cit. pág. 97.[back to the text]

7. Hamid Dabashi, Close Up: Iranian Cinema, Past, Present, and Future, Verso, 2001, pág. 41. [back to the text]

8. Goli M. Rezai-Rashti, “Transcending the Limitations: Women and the Post-revolutionary Iranian Cinema”, Critique: Critical Middle Eastern Studies , vol. 16, núm. 2, 2007, págs. 198 [back to the text]

9. Shahla Lahiji, “Chaste Dolls and Unchaste Dolls”, en Women in Iranian Cinema since 1979, edited by: Richard Tapper, I. B. Tauris , 2002 [back to the text]

10. The Islamic women’s dress code which states that a woman in public must cover most of her body. The hijab is sometimes derived from religious law and sometimes related to one’s social contract and situation. [back to the text]

11. Ziba Mir-Hosseini, “Iranian Cinema: Art, Society and the State”, Middle East Report (MERIP), núm. 219, 2001, págs. 26-29.[back to the text]

12. Alberto Elena, Los cines periféricos: África, Oriente Medio e India. Paidós. Barcelona, 1999. pág. 276 [back to the text]

13.Chador is a typically Iranian female street wear, consisting of a simple semi-circular piece of fabric open at the front that is worn over the head, covering the entire body except the face. [back to the text]

14. Ronald Robertson, “Glocalización: tiempo-espacio y homogeneidad-heterogeneidad”. Cansancio del Leviatán : problemas políticos de la mundialización. Trotta, Madrid. 2003.

Also for more information on the term Glocalization, which combines the words globalization and localization, it first appeared in the late 1980s in the articles by Japanese economists in the Harvard Business Review. According to sociologist Roland Robertson, who is credited with popularizing the term, glocalization describes the attenuating effects of local conditions on global pressures. Véase: Margaret Rouse, “Glocalization Definition”, 2013. [back to the text]

15. Negar Mottahedeh, “‘Life Is Color!’ Toward a Transnational Feminist Analysis of Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s Gabbeh”, Signs, núm . 30, 2004, págs. 1403-1428 [back to the text]

16. Hamid Naficy “Veiled vision/powerful presence: women in post-revolutionary Iranian cinema” Life and art the new iranian cinema, Rose Issa, Sheila Whitaker, National Film Theatre / The British Film Institute, 1999, p:44-45-46 [back to the text]

17. Rose Issa, “Real Fictions”, 2004. [back to the text]

18. Mazda Moradabbasi, La Señora de zagros (Banui az Zagros), Farabi Cinema Foundation (FCF), 2014 [back to the text]

19. Interview by Milos Srehlik with Rakhshan Banietemad. [back to the text]

The article was presented at the film studies conference on March 13, 2020.

Toward Cinematic Anthropocene

Read More

Psychological Dimension of Filmmaking

Read More

Film Studies Conference

Read More

IRANIAN WOMEN CINEMA: THE FEMALE REPRESENTATION NARRATED BY IRANIAN WOMEN FILMMAKERS

Read More

ANAL STAGE OF PSYCHOSEXUAL DEVELOPMENT IN SCREENWRITING: EVOLUTION OF TECHNIQUE

Read More

International Film Study Conference

Read More

CAN WE MEASURE HAPPINESS* OF FILMMAKING?

Read More

Calculators

Read More

Do non-artistic factors affect film selecting?

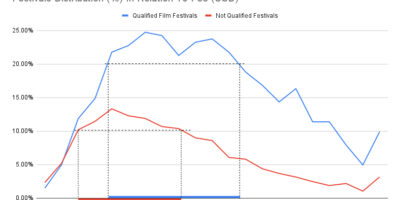

Read More