In the natural sciences, we often see how many phenomena emerge as a by-product of the interactions or collisions between particles or elements. Similarly, we can assume that the poetics of cinema did not arise from deliberate intention. Rather, art can be considered a vibrant blossoming on the remnants of what once was.

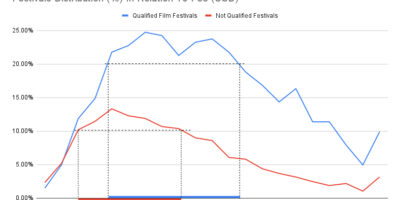

Academic publications that aim to systematically present film theory and its history typically address the relationship between cinema and art. When we describe film as either art or as an industry, business, or market, we can assign different essential characteristics to this concept or phenomenon. We will look at this ratio through the history of strategies to lure viewers into movie theaters.

Pursuit of box office receipts: history perspective

Romanticism significantly raised awareness of aesthetic values and highlighted the artistic and life significance of various art forms, including literature, music, theater, and painting. The 19th century, with its mass-produced literature, inspiring theater, and impactful music, helped prepare the public and create a mass audience ready for the emergence of cinema.

The history of cinema can be viewed as a century-long effort to attract movie theater attendance. This involves the actions of the major film industry leaders of their time. The film industry fights fiercely for audience attention and investment. At the same time, noteworthy examples of auteur cinema, conceptual films, and even counter-cinema thrive on the successes of the mainstream film industry. This complexity is why cinema, much like prostitution, is multifaceted and contradictory.

One of the earliest strategies to broaden the audience for cinema, while appealing to the more respectable classes, was the adaptation of literary works. This approach elevated the film’s status from mere entertainment to a claim of high art. Another significant development was the advent of sound in cinema, which coincided with the Great Depression. The emergence of sound led to discussions about the potential decline of cinema as an art form, often referred to as the “death of The Great Dumb.”

The film industry then faced a new challenge with the rise of television. Cinema screens became not only larger but also more vibrant with color. Attracting younger audiences, particularly teenagers, became a crucial focus for the movie-producing industry. In the digital age, we are observing various strategies designed to target specific audiences, particularly fans of cult franchises and biopics. These strategies influence the length, content, and techniques used in films.

Art, power, and sacredness

Johan Huizinga observed that artwork has often been connected to the sacred world, embodying a sense of power—magical power, sacred meaning, and a representative identity associated with cosmic significance. It holds symbolic value and conveys a sense of sanctification. Over time, art has increasingly supplanted religion, assuming the role of a secular belief system. As art critic Boris Groys noted, contemporary art centers in European cities play the role of medieval temples.

Martin Scorsese’s controversial statement claiming that Marvel movies are not cinema reflects a judgment about deeper involvement in what he considers higher art. This perspective highlights the evident hierarchical structure within the contemporary art and cinema institutions, a concern that Marcel Duchamp pointed out over a century ago. The prevailing discourse categorizes certain works as “high art” or “art films.” History, including the realms of art and film, is written by winners, as many forgotten artifacts from media archaeology also compellingly demonstrate.

It seems that everything is projected on screens—whether in movie theaters, on television, or through smartphones. This includes classic films, radical avant-garde pieces, sitcoms, soap operas, and other lowbrow consumer products. This aspect of cinema sets it apart from other forms of visual art, which are typically displayed in museums or galleries. In these spaces, objects are recognized as art, and their creators are labeled as artists. In contrast, aesthetically pleasing items that are mass-produced are found on retail counters, categorized as goods, with their creators referred to as designers. This distinction appears straightforward, but in cinema, the division is not as clear-cut. Cinephile film clubs can serve a similar museum function, while film festivals can act like galleries. However, the situation is more complex than it seems.

In cinema, compared to the contemporary art system, the scattered, ephemeral, and self-organized collectives are often marginalized and coopted as enduring reserves. Meanwhile, major film festivals have their own industrial platforms and film markets. While arthouse programming exists there, it is typically limited by mainstream constraints, with agendas frequently influenced by socio-political conjuncture. It is important to remember that in its early years, the Cannes Film Festival was referred to as “Hollywood’s vacationing bitch.” The emerging network of European film festivals largely adopted the studio approach to cinema, complete with its emphasis on stars, opulence, and red carpets.

In this context, it is important to mention what is referred to as “Second World Cinema,” particularly as described in the manifesto by Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino titled “Towards a Third Cinema.” European auteur cinema primarily represents a reproduction of bourgeois passivity and reinforces cultural colonialism. Its formal self-reflexivity, along with the combination of “edgy themes,” often leads to the marginalization and taming of peripheral voices by victimizing entire groups and communities from postcolonial countries.

The privilege of belonging to the world of art and the sacred domain is fundamentally a matter of power and hierarchy.

Guy Debord highlighted the class division between authors and spectators, as well as between writers and readers. Even in Walter Benjamin’s time, there was concern about the blurring of boundaries between authors and their audiences. This issue arises when art becomes overly commercialized and sinks into the mainstream. Today, this situation often manifests itself when consumers create content—such as writing or filming—intended for later consumption and monetization. Debord’s concept of class division between authors and viewers has evolved into a distinction between content producers and consumers, particularly in visual media. The maximum aspiration for many consumers is to become content creators thereby gaining some degree of power. However, within certain digital environments and their algorithms, any form of struggle or confrontation is effectively excluded.

Art remains an elusive meta-industrial sphere. At the same time, institutionalized art remains sacralized. Thus, the sacred and metaphysical becomes tamed in the secular world. For example, the criterion for classifying a film as art should be its inclusion in the turnover of aesthetic analysis as an object of art. This is a kind of academic recognition.

Film studies publications often analyze a wide variety of films, encompassing everything from the poetic examination of soap operas and worst films to the critique of highbrow arthouse cinema. Any movie that captures the masses’ attention, whether positively or negatively, becomes a topic of inquiry in academic journals. This reflects a self-regulating filtering system known as the “Sacred Screen“.