As it is well known, cinema was invented in the Celestial Empire, and it was only technically upgraded in Paris …

BRIEF HISTORY

Today, when we talk about national cinema or its national characteristics, we should take into account that Chinese cinema in its history has not been isolated from external cultural influences. Domestic-oriented film studios emerged in China as early as the 1920s when it became clear that it was very difficult for people of non-Chinese origin to reach local audiences. The film companies founded by Western concessionaires were taken over by local entrepreneurs who better understood audience expectations.

Qufu movie theater, Shandong

The subsequent history of Chinese cinema is divided into periods defined by the country’s political history. Any of these phases were accompanied by the integration of foreign influences in the sphere of the preservation and reproduction of national identity, aside from the Cultural Revolution (1966-1977), which Chinese film textbooks call a gap.

On the one hand, the history of Chinese cinema was a struggle against Westernization before the founding of the PRC in 1949. On the other hand, it was an attempt to enter the international film market. In the following years, film production was accompanied by strict communist party control and censorship that led to the suppression of traditional genres, such as wuxia, and to a bias toward realism.

The period of the fifth and sixth Chinese filmmakers’ generations falls in a time of reform and openness. It was a period when Chinese films received numerous awards at the world’s most prestigious festivals and were distributed internationally. In one way, this was due to the romantic interest and curiosity of “civilized Europe” to other cultures, and the desire to have them in a household. In another way, this explains the sense of paternalism, i.e. the need for the presence of the alien, which allows for preserving identity

However, the history of Chinese cinema cannot be considered separately from the cinematography of Hong Kong and Taiwan. Each of the three Chinese-language cinema has a distinctive political and historical experience. Representatives of Hong Kong, Taiwanese, and mainland cinema have been involved in co-productions in recent decades.

Today, China’s rapidly growing film industry is the second-largest in the world after the United States. Chinese investment has come to Hollywood. China is actively developing not only the domestic film market but also successfully operating in the international movie distribution market and streaming platforms. China attaches great importance to the ability of cinema to integrate with political influence channels, including international ones. China’s strategic goal is to build a “powerful cultural state,” that is, a state capable of projecting its cultural tradition outward, turning culture into one of the resources of foreign policy and thus gaining a significant potential of “soft power”.

LAYER OF SHORT FILMS

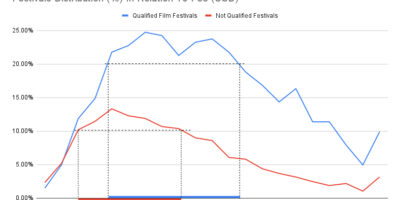

A study of the national cinema would be incomplete if we conclude only from famous directors or movies that make it to the big box office or top festivals. A huge stratum of micro-budget auteur films, usually short films, remains out of focus. We based our analysis on more than 150 short films made in the PRC, submitted to the Nefiltravanae Kino Film Festival in the last five years.

The themes of Chinese short films are essentially the same as those of other regions of the world, with a shift of one kind or another. Sometimes you could replace Chinese protagonists with European ones, and move the location, but the essence wouldn’t change. By the way, the festival received a significant number of abstractive films in which the place is imaginary and the time may not exist. What is important for us is the refraction of Chinese routines and events in the films. We can’t but mention a special stratum of films made by Chinese migrants or repatriates.

Long Yearning (dir. Elliot J Spencer, 2017)

In this regard, it is worth beginning the description of notable short films with Li Bo’s adaptation of an ancient Chinese poem. Long Yearning (dir. Elliot J Spencer, 2017) is a cinematic exploration of Chinese workers’ lives and the industrial routine nature. One can feel this longing exposure trapped between the means of production and the overwhelmed commodities, including floating manufacturing waste. The picture of hopelessness and closeness emerges from a mosaic of master shots and a close gaze into the nameless cogs of this machine, on the one hand, and the frightening enormity of the state-party plan on the other.

The Big Brother (dir. Prada Wang, 2020)

The Big Brother (dir. Prada Wang 2020) is the story of a “spa center that offers turtle exfoliation”. The film is about the meaningless, absurd, boastful, and conceited lives of several young people from northeastern China. Their characters and relationships serve as metaphors for Soviet politics. The film intertwines reality, dreaming, delusion, and conception, attempting a direct scene change between the dreams of the various characters. The film is essentially an artistic record of the rapid transformation of Chinese society. The setting of luxury and wealth serves only as a curtain behind which the omnipresent Big Brother cameras are hidden.

Why Are We Unhappy in Cities? (Zhao Gang, 2020)

The themes of the city and urban life occupy a special place in Chinese cinema. Zhao Gang’s unequivocally titled “Why Are We Unhappy in Cities?” (2020) This parable movie explores the relationship between city inhabitants and objects. When people create objects (goods), they also become slaves to those objects and even alienated from the objects themselves – a scene in which the female protagonist works part-time as a mannequin in a store window accurately interprets this idea. The endless running and walking in a circle, the dependence on things leads the main character to the only salvation – an unconscious escape to nowhere.

The Bubble (Haonan Wang, 2020)

The theme of the city is developed in Haonan Wang’s art-house short film “The Bubble” (2020). The urban environment becomes the scene of the relationship between a man and a woman. Nature is displaced from a lifeless, functional space. The only green and succulent plants are greedily and excessively consumed by the man under the control of the woman. Orgasm and consumption become interdependent parts of the one whole, the human soul is being perpetuated in a glass bubble.

We can view the entire story as a ritual. A sacred ritual of love. A relationship between the offerer and God. In the film, the man wants to give every bit of him to the woman, and she accepts it all. It’s natural and not overwhelmingly sentimental. The woman knows that the man is sacrificing for her. She’s grateful, yet she’s used to it. She knows it’s tough to be apart, but she yearns for the final result. The final result turns out to be the desire for life itself. Or, the basic instinct of us animals (Haonan Wang).

The Elevator (dir. Jiang Dong, 2022)

The transformation of social relations is accompanied by challenges to justice and to the relationship between the common good and the private interest. This is especially evident in cities, where people live literally on top of one another. The domestic issue of elevator installation can reveal complex issues of morality, politics and human interaction. According to a statement of Jiang Dong, director of The Elevator (2022): the same thing and the same group of people produced completely different results due to changes in initiators and policies, which could easily happen in China. Lin Hai is not against installing elevators, but against this ever-changing society. What the neighbors agree to is not installing an elevator,either, but going with the flow in this changing society, which is the simplest way to survive.

Industrial noise invades a silent temple. The Sarira (2021) by Mingyang Li depicts the collision of the rapidly evolving city and what’s left of what was once sacred and ancient. A monk can’t find respite after a toothache leaves him unable to chant the sutras and he can’t escape the sounds of nearby construction. A bad tooth, an ancient Buddha, a temple, and a silent monk. Yi Dao starts his survey of this world. Face death, face people, and get back in society, be himself one more time. The film captures religious solemnity in black-and-white imagery and argues about the confusion and direction of identity and faith at odds with the pain of development in the modern world.

So far, so close (dir. Nicolas Vimenet, 2023)

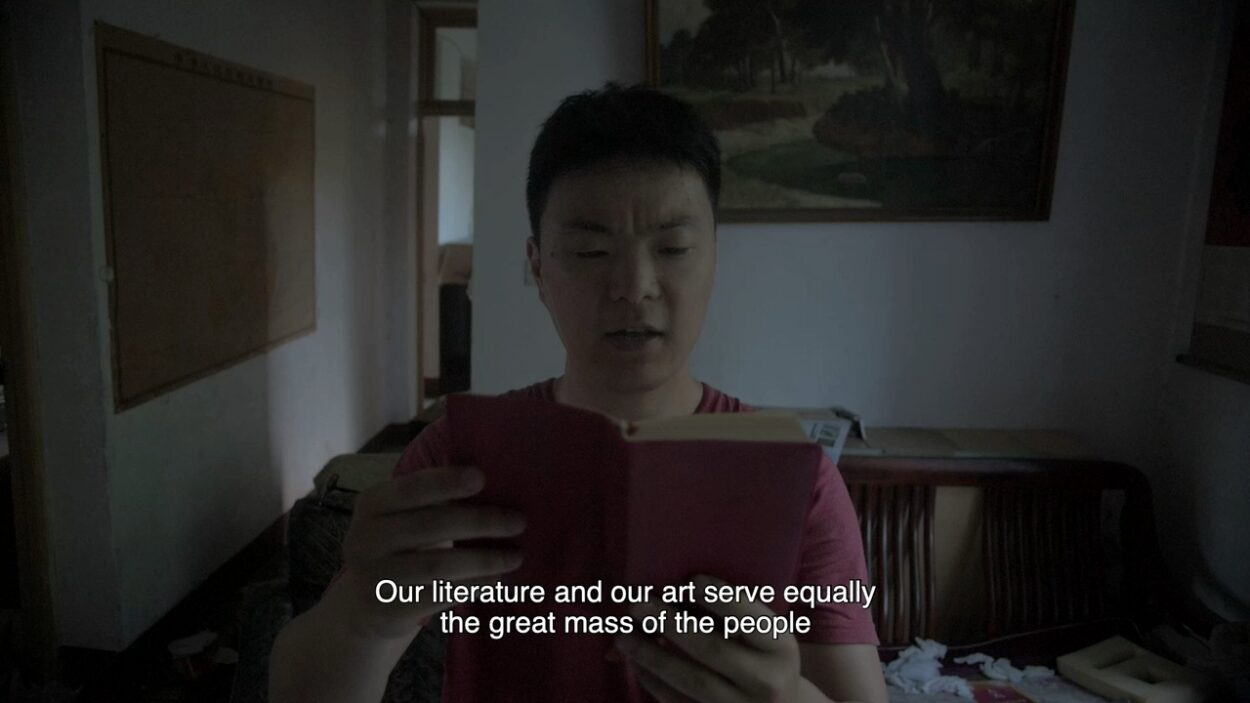

The son of a Chinese immigrant who left the country more than 20 years ago, Nicolas returns to the bedside of his seriously ill grandmother (So far, so close (2023) by Nicolas Vimenet). He arrives in his historic homeland. After receiving a European cultural education in France, he tries to understand the new world he has discovered as an open book. This Eastern book is full of riddles and reticences, unlike Mao’s quotation book. Nicolas’s recitation of the red book, a kind of gospel of the 1968 Paris Spring, is a European improvisation far from the original. He is corrected by his grandmother, an honored party leader of the Cultural Revolution. She and her memory serve as a medium between past and present.

The list of the short films:

- Long Yearning (dir. Elliot J Spencer, 2017) – 24 min;

- The Big Brother (dir. Prada Wang, 2020) – 40 min;

- Why Are We Unhappy in Cities? (Zhao Gang, 2020) – 27 min;

- The Bubble (Haonan Wang, 2020) – 14 min;

- The Elevator (dir. Jiang Dong, 2022) – 16 min;

- The Sarira (dir. Mingyang Li, 2021) – 28 min;

- So far, so close (dir. Nicolas Vimenet, 2023) – 27 min.

ALL ARTICLES: