In an era dominated by algorithmic consumption and corporate-controlled narratives, indie filmmakers stand at a crossroads within a labyrinth. Their work, often born from a desire to challenge mainstream ideologies, exists within a capitalist framework that commodifies dissent. This article critiques the role of indie filmmakers in a consumer society, interrogates their capacity to survive outside the system, and explores whether they can subvert—or even dismantle—the structures that constrain them. By tracing the evolution of social and political thought from the 20th century to today, we uncover both the limitations and possibilities of independent artistry.

Historical Overview: From Critique to Co-optation

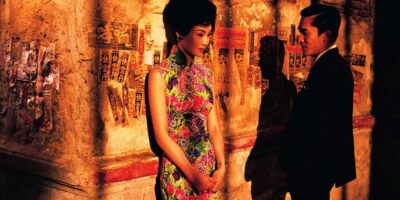

The seeds of indie filmmaking’s ethos were sown in early 20th-century avant-garde movements, such as Soviet montage cinema and French surrealist films. The Frankfurt School, notably Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer in Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947), condemned mass culture as a “culture industry” that pacified audiences through commodified entertainment. By the 1960s, the French New Wave—Jean-Luc Godard’s La Chinoise (1967), Agnès Varda’s Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962)—used fragmented narratives and political allegory to challenge Hollywood’s hegemony.

The 1970s New Hollywood era saw directors like Martin Scorsese (Taxi Driver, 1976) and Robert Altman (Nashville, 1975) embedding critiques of American excess into mainstream cinema. Yet the neoliberal turn of the 1980s-90s recast dissent as a marketable brand. Sundance, founded in 1985, evolved from a rebel campfire into a studio talent pipeline, while films like Pulp Fiction (1994) wore their “indie” label as a badge of edgy marketability.

The digital age promised liberation but delivered new constraints. Platforms like YouTube democratized distribution but drowned filmmakers in an ocean of content. Streaming giants like Netflix repackaged indie aesthetics as “niche” products—The Florida Project (2017), a critique of poverty, became a profit stream for Amazon. Recent works like Boots Riley’s Sorry to Bother You (2018) and Jane Schoenbrun’s We’re All Going to the World’s Fair (2021) dissect digital alienation, while Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite (2019) and A24’s Everything Everywhere All At Once (2022) blend surrealism with anti-capitalist themes, only to see their messages diluted by merchandising.

Scholars like Nancy Fraser (Cannibal Capitalism, 2023) argue that capitalism “devours its critics, then sells their bones as artisanal fertilizer,” while Mark Fisher’s posthumous Postcapitalist Desire (2020) laments the erosion of systemic alternatives. These tensions mirror indie film’s struggle to balance art and survival in a world where even rebellion is monetized.

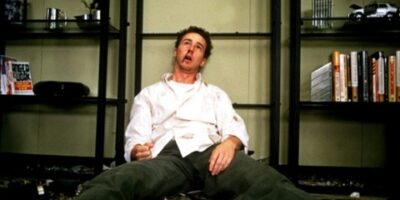

Fight Club (1999) by David Fincher

Slaying the Leviathan? Evidence of a Mirage

History mocks the notion of “destroying” capitalism. Punk’s anarchy became Hot Topic merch; Fight Club’s anti-consumerism birthed branded soap. Naomi Klein (No Logo, 2000) notes that resistance often becomes “a market segment.” TikTok repackages political cinema into 15-second clips, stripping context for clicks.

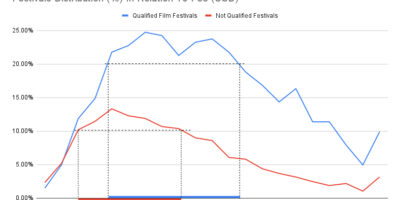

Other evidence of co-optation may include Streaming Algorithms as well as major Film Festival Pipelines. Netflix’s “indie” category markets films as “quirky” content, divorcing politics from profit. Sundance films like CODA (2021) are acquired by Apple TV+, sanitizing their indie ethos.

Today’s indie filmmakers face a Faustian bargain: to sustain their craft, they must engage with systems that neutralize their critique. Social media reduces narratives to clickbait, crowdfunding turns artists into influencers, and festivals prioritize “marketable activism” (e.g., trauma-driven poverty porn). Even films about marginalization risk tokenization, repackaged as diversity checkboxes for corporate virtue signaling. The result is a cycle of complicity: indie films critique consumerism yet depend on its mechanisms for visibility. As filmmaker Ava DuVernay noted, “Indie is a mindset, not a budget”—but without financial autonomy, the mindset bends to market logic.

This does not negate resistance but reframes it: systemic change requires erosion, not revolution.

Surviving Outside the System: Pathways to The Cooperative Filmmaking Ecosystem

Is survival possible without capitulation? History offers cautious optimism for cooperative models, alternative funding, and decentralized distribution. Yet these strategies require sacrifices: limited budgets, smaller audiences, and immense labor. Survival outside the system is possible, but sustainability demands redefining success beyond commercial metrics.

For sure, indie artists are not able to “destroy” the consumerist system on their own. As we have seen above, global capitalism adapts to absorb dissent. However, they can erode its cultural hegemony by creating counter-narratives, fostering critical audiences by partnering with grassroots organizations, and building parallel structures. Following the Zapatistas’ use of media for autonomy, indie networks could create self-sustaining ecosystems—production co-ops, alternative festivals, educational hubs.

Indie filmmakers can be not saviors but catalysts, to say it optimistically, ye. Their role is to expose contradictions and amplify marginalized voices, eroding trust in predatory platforms, to сenter narratives that reject capitalist tropes—e.g., stories without villains, resolutions, or growth arcs. An example of the latter is Aftersun (2022) that eschews traditional conflict, focusing instead on emotional ambiguity.

We have the power to experiment with form to transgress sterilization and taming. As it occurred with Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite (2019) or Boots Riley’s Sorry to Bother You (2018), for example. Yes, satire and surrealism to critique class structures, sparking public discourse do not work today. Probably, the direction is to unmarketable and algorithm-resistant art. In the face of atomization, the author will not be able to go it alone. He or she will not succeed. Today, the counter-artist should work within symbiotic anarchist and cooperative partnerships.

Beyond the Myth, Toward Subversive Praxis

Indie filmmakers cannot demolish the Leviathan labyrinth but can abolish it by carving new corridors within.The Cooperative Filmmaking Ecosystem is no utopia but a pragmatic raft—a way to stay afloat while subtly redirecting the storm’s energy. By decentralizing power, reimagining labor, and aligning with broader movements, filmmakers can transform the labyrinth from within. It requires embracing blockchain’s potential without fetishizing it, rejecting viral metrics, and aligning with movements larger than cinema. As Astra Taylor’s Debt Collective (2020) shows, systemic change begins with building alternatives that exist alongside and against the dominant order.

Indie filmmakers must ask: Will we be co-opted, or will we become architects of a new cultural language? The answer lies not in isolation, but in collective reimagining.

ALL ARTICLES: