This article traces the film festival movement from its origins in political propaganda and post-war cine-clubs to its current digital era. It explores how technology—from video to AI algorithms—has reshaped submission processes and created new challenges of curation and commercialization. The piece examines global perspectives and future trends, arguing that festivals must balance technological change with their core mission of fostering human connection through cinema.

Imagine a world without film festivals. For today’s filmmakers, it’s almost impossible. But this powerful, global ecosystem didn’t appear overnight. Its story is a rich tapestry, deeply woven with politics, technology, and a simple, enduring love for cinema. It all started not in grand palaces, but in small, smoky rooms among friends who believed in the magic of the moving image.

Long before the red carpets and international markets, there were film societas. These were the true cradle of the festival movement. In cities like Paris and London, groups of film lovers, artists, and intellectuals would gather in basements and cafes to watch and passionately debate movies, seeing them as art long before Hollywood established its commercial dominance. This was especially strong in Europe after World War I, a period of immense social and artistic fermentation. The first major international film festival in Venice in 1932 was, in a way, an extension of this idea, but it was immediately co-opted by powerful political forces. It was launched by the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, who shrewdly used it as a tool for propaganda, to showcase the cultural strength and unity of his fascist regime. The political stakes became undeniable when the festival’s top prize in 1936 was awarded to Leni Riefenstahl’s Nazi German film, “Triumph of the Will.” This caused such an uproar that France, along with other Western democracies, decided to create its own festival as a direct response: the Cannes Film Festival, envisioned from the start as a “festival of free nations.” So, from its very inception, the international film festival movement was not just about art; it was a battlefield of competing ideologies.

After the devastation of the Second World War, the role of cine-clubs evolved but remained vitally important. They transformed into essential hubs for cultural recovery and democratic education. In Latin America, for example, cine-clubs in the 1950s and 60s were the breeding grounds for the politically charged “New Latin American Cinema.” They were safe spaces where filmmakers like Glauber Rocha from Brazil or Fernando Solanas from Argentina could show work that boldly challenged military dictatorships and explored deep-seated social injustice, far from the control of commercial circuits and state censorship. This grassroots spirit, focusing on community and unfiltered expression, finds its echo in various modern projects that continue to champion grassroots cinema. Meanwhile, in the Soviet Bloc, state-sanctioned film clubs became one of the few avenues where citizens could access a curated selection of foreign films, offering a carefully managed window to the outside world.

Technology has always been the great disruptor and enabler of the festival world. The arrival of sound and then color in cinema turned major festivals into glamorous showcases of the latest technological marvels from Hollywood and European studios. Then came television. Suddenly, festivals were no longer the only place for a global audience to see new films, but they quickly became a crucial, centralized market for selling films to this new powerful broadcast medium. The video revolution of the 1980s was an even bigger democratizing force. The VHS tape and the portable video camera made films drastically cheaper to produce and easier to ship globally, allowing a massive wave of independent, experimental, and politically radical films to bypass traditional gatekeepers and reach festival programmers. This democratized filmmaking like never before but also began to flood selection committees with submissions, creating a new problem of abundance.

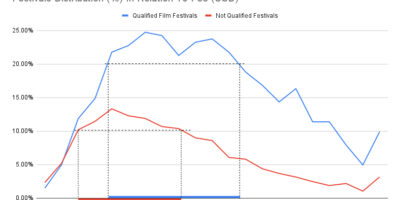

Then, the internet changed everything again, launching a second wave of democratization. In the early 2000s, a platform called Withoutabox appeared, fundamentally altering the logistics of film submission. For the first time, a filmmaker sitting in a small apartment could submit their film to hundreds of festivals worldwide from a single online profile. It was revolutionary. Later, FilmFreeway took this idea and made it even smoother, more intuitive, and more accessible. Today, FilmFreeway lists over 8,500 festivals and is used by more than a million filmmakers worldwide. This created a “global village” for festivals, letting a director in Argentina as easily submit to a small festival in Korea as to a major one in Europe. But this convenience had a significant downside. It led to an avalanche of submissions, making it incredibly hard for individual films to stand out in the digital crowd, and arguably gave rise to a multitude of “pay-to-play” festivals with questionable prestige and selection rigor.

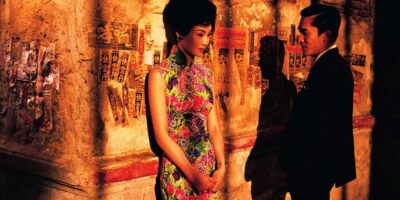

The festival story is far from just a European and American tale. Across the globe, festivals have emerged as powerful assertions of cultural and political identity. The Pan-African Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou (FESPACO) in Burkina Faso, founded in 1969, became a monumental platform for African filmmakers to tell their own stories after decades of colonial narrative control. It was a direct declaration of cultural sovereignty. In Asia, the International Film Festival of India started as early as 1952, the same year as the Berlin International Film Festival, which was itself founded in a city physically divided by the Cold War, intended to be a “shop window to the Free World.” The Tokyo International Film Festival emerged in the 1980s as Japan confidently asserted its soft power as a new economic giant. Similarly, the Mar del Plata International Film Festival in Argentina, created in 1954, served as a cultural beacon for Latin America. Each of these festivals carried the distinct social and political weight of their region.

The digital revolution did not stop with submission platforms. The rise of social media and YouTube created a parallel universe of film discovery and discourse. Filmmakers could now build an audience online long before their film ever played at a festival. A short film going viral on YouTube could catapult a director to fame, forcing festival programmers to take notice. This shifted some power away from traditional gatekeepers. However, it also created a new form of pressure: the need for constant self-promotion and the creation of a “brand” around one’s work. Furthermore, YouTube became both a competitor and a supplement to festivals; why wait for a festival slot when you can reach millions directly?

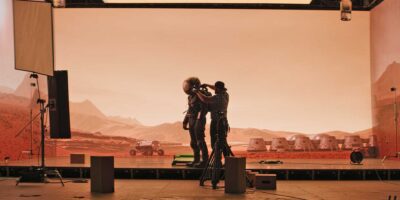

This brings us to the latest technological frontier: neural networks and artificial intelligence. AI is beginning to influence the festival circuit in complex ways. On one hand, it is a powerful new tool for filmmakers, used to create stunning visual effects, de-age actors, or even write scripts. On the other hand, it presents an existential question for festivals: how do we categorize and judge a film primarily generated by an algorithm? More insidiously, we face a growing socio-political problem tied to algorithms. The digital platforms we rely on—from FilmFreeway to YouTube to social media feeds—are governed by opaque algorithms designed for engagement, not for artistic curation. These algorithms can create invisible “filter bubbles,” silently shaping which films get recommended, which trailers go viral, and ultimately, which narratives gain cultural traction. This automated pre-selection can unconsciously homogenize taste and marginalize unconventional, slow-burn, or politically uncomfortable films that don’t fit the algorithmic mold for virality. It’s a new, digital form of censorship, not by a government committee, but by a lines of code optimized for clicks.

Today’s festival world navigates a complex web of modern problems. Political pressure remains acute; after the start of the war in Ukraine, major European festivals banned official Russian delegations, demonstrating how quickly geopolitics can isolate artists and force festivals to take a stand. The problem of commercialisation is more pronounced than ever. As festivals grow into massive industries, corporate sponsors and red-carpet glamour can sometimes overshadow the core artistic mission of discovering new and risky voices. The submission overload from digital platforms creates a bottleneck, where quality films can be buried in a sea of content, straining the volunteer-based selection committees of smaller festivals. Furthermore, the question of sustainability is key—not just environmental, concerning the carbon footprint of international travel, but also financial, for both the festivals themselves and the independent filmmakers who must fund their own travels. Finally, the rise of streaming platforms poses a fundamental question: what is the unique role of a physical festival when audiences can watch thousands of films from the comfort of their home?

Looking ahead, the future appears to be hybrid and community-focused. The blend of physical and online festival experiences will likely become standard, making cinema more accessible while preserving the irreplaceable magic of a shared audience. The role of carefully curated, niche events and the spirit of classic cine-clubs will grow in importance, offering a human-curated antidote to the algorithmic chaos of streaming and social media. Festivals will be less about mere premieres and more about creating unique, live experiences—meaningful conversations, hands-on workshops, and genuine community building—that you simply cannot replicate on a screen at home. Despite all the technological and political shifts, the core idea that started in those small, passionate cine-clubs—that cinema is a conversation, a shared human experience—will undoubtedly remain its beating heart.

Bailey Milan