Introduction

The concept of the “death of the author,” introduced by Roland Barthes in 1967, destabilizes the Romantic ideal of the solitary genius, asserting that meaning emerges not from the creator’s intent but through the reader’s interpretation. For indie filmmakers—often celebrated as auteurs who imprint personal visions onto their work—this idea invites critical reflection. As artificial intelligence (AI) reshapes filmmaking, from script generation to post-production, the question of authorship grows urgent: Can a filmmaker still claim to “speak” when tools and collaborators mediate every frame? This essay critiques the evolving discourse around cinematic authorship, tracing its theoretical roots, examining contemporary debates, and speculating on AI’s impact. By interrogating the critiques of authorship, the role of cinematic language, and the possibility of new discourses, we explore how indie filmmakers might navigate a landscape where authorship is both fragmented and redefined.

Historical Overview: From Auteur Theory to Poststructuralism

The mid-20th century saw the rise of auteur theory, championed by French New Wave critics like François Truffaut and Andrew Sarris. This framework elevated directors such as Alfred Hitchcock and Jean-Luc Godard to the status of authors, framing their films as extensions of personal vision. Auteurism romanticized the director as a sovereign creator, a myth that persists in indie cinema’s cult of the visionary filmmaker.

Poststructuralist thinkers dismantled this myth. Barthes’ The Death of the Author (1967) argued that texts are shaped by readers, not writers, while Michel Foucault’s What is an Author? (1969) redefined authorship as a social construct—a “function” that organizes cultural discourse. These ideas challenged the auteur’s authority, positioning cinema as a collaborative, intertextual practice.

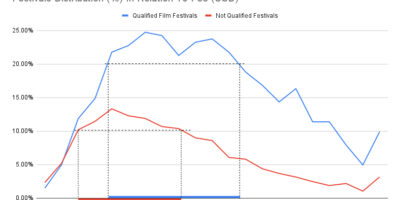

In the 21st century, digital media further fragmented authorship. Henry Jenkins’ Convergence Culture (2006) highlighted participatory fandoms and transmedia storytelling, while platforms like TikTok and YouTube democratized creation. Recent scholarship, such as Sarah Atkinson’s From Film Practice to Data Process (2020), examines how algorithms influence film production, and Kate Eichhorn’s The End of Forgetting (2019) critiques digital ownership. These works underscore the tension between individual agency and systemic forces in defining authorship.

Auterism Under Siege

Today, indie filmmakers operate in a paradoxical landscape: auteur branding is commodified (e.g., “A Greta Gerwig Film”) even as collaboration and algorithmic curation erode individual control. Streaming platforms like Netflix market films using director-driven hype while data analytics dictate content trends. Meanwhile, collectives like the Dakota-Kid film group or crowdfunded projects like Blue Ruin (2013) challenge the myth of the lone creator.

Criticism of Authorship in Cinema

Critics argue that auteur theory obscures cinema’s inherently collaborative nature. The director’s vision is filtered through cinematographers, editors, and actors—a reality indie filmmakers often downplay to secure funding or critical legitimacy. Film scholar David Bordwell, in Reinventing Hollywood (2017), notes that even iconic auteurs like Hitchcock relied on teams of writers and technicians. Recent movements, such as the #PayUpHollywood campaign, further highlight systemic inequities in attributing credit, questioning who “owns” a film’s success.

Are Codes and Conventions Impersonal?

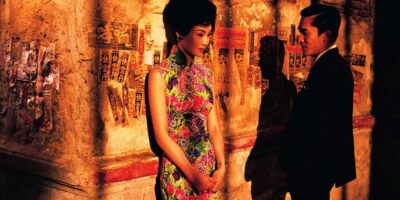

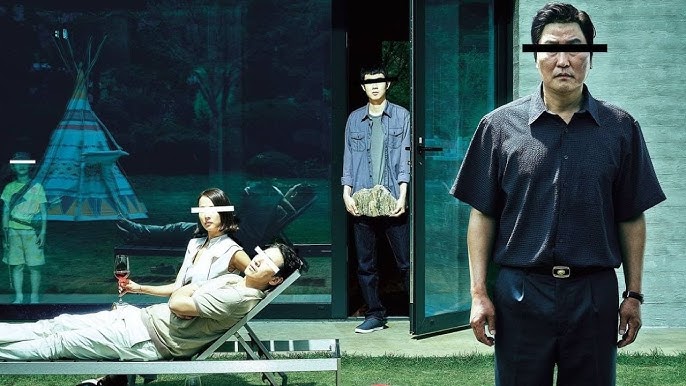

Filmic codes—genre tropes, shot compositions, narrative structures—are inherited from a shared cultural lexicon. Yet auteurs repurpose these codes to forge new meanings. Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017) weaponizes horror conventions to critique racism, while Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite (2019) subverts class satire through thriller pacing. These examples reveal codes as malleable tools, not deterministic chains. As media theorist Lev Manovich argues in The Language of New Media (2001), conventions are “negotiated, not dictated”—a dynamic amplified in indie cinema’s experimental ethos.

Parasite (2019) by Bong Joon-ho

Does Language Speak for the Author?

Structuralism posits that language precedes and shapes the author. In cinema, the “language” of mise-en-scène, sound, and editing mediates the filmmaker’s voice. However, poststructuralists emphasize that meaning emerges dynamically between text and audience. The ambiguous ending of Robert Eggers’ The Lighthouse (2019) invites myriad interpretations, embodying Barthes’ “writerly text.” Here, the filmmaker encodes signals, but the viewer decodes them through personal and cultural lenses.

Who Speaks? Foucault, Barthes, and the Auteur Function

Foucault’s “author function” explains why society attributes coherence to a director’s work, even when collaborators abound. Labeling a film “Lynchian” invokes curated tropes (surrealism, psychological dread) that serve marketable and critical purposes. For indie filmmakers, this creates a paradox: their “voice” is both a personal imprint and a discursive construct shaped by reception.

New film discourses can advent by engaging with existing systems. Jean-Luc Godard’s jump cuts in Breathless (1960) shattered continuity editing, forging a new visual grammar. Similarly, Sergei Eisenstein’s montage theory redefined narrative rhythm. These auteurs did not invent from nothing; they reshaped inherited codes. Contemporary examples include Barry Jenkins’ use of intimate close-ups in Moonlight (2016) to center Black queer subjectivity, challenging dominant cinematic narratives.

Cinema’s discursivity—its power to shape cultural narratives—has long been critiqued. Feminist scholars like Laura Mulvey (Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, 1975) argue that Hollywood’s male gaze perpetuates patriarchal norms. Similarly, indie films like The Watermelon Woman (1996) by Cheryl Dunye critique archival erasure of Black lesbian histories. These works expose how dominant discourses marginalize alternative voices, urging filmmakers to interrogate their role in perpetuating or dismantling systems.

AI and the Future of Auteur Cinema

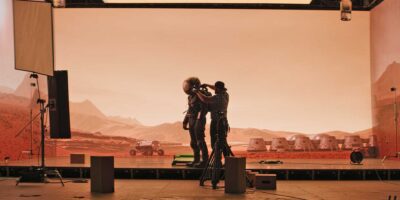

AI’s integration into filmmaking—scriptwriting (ChatGPT), editing (Runway ML), and deepfakes—poses existential questions. Tools like OpenAI’s GPT-4 can generate dialogue, while AI-driven platforms like Artbreeder design visuals. For example, the AI-scripted short Sunspring (2016) blends absurdity with uncanny creativity. Here, the human role shifts from sole creator to curator, selecting and refining algorithmic output. Andres Guadamuz’s AI and Copyright (2023) argues that current laws prioritize human “input,” but ethical gray areas persist. If an indie filmmaker uses AI to generate a screenplay, who owns the work? The answer may redefine auteurs as orchestrators of human-machine symbiosis. AI could democratize filmmaking, enabling low-budget creators to simulate costly effects. Yet it risks homogenizing aesthetics. Projects like Refik Anadol’s

Leviathan’s Dream: Indie Filmmakers as Disruptors

If cinema is “Leviathan’s dream”—a metaphor for its power to shape collective consciousness—indie filmmakers are its lucid dreamers. They challenge dominant narratives, as seen in: Lynne Ramsay’s fragmented narratives (You Were Never Really Here), rejecting Hollywood’s linearity. Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s surreal ethnographies (Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives), blending folklore with experimental form.

Assumed, their role is not to claim authorship but to interrogate it, using collaborative, hybrid, or AI-augmented methods to expand cinema’s discursive possibilities.

The death of the author is not an endpoint but a call to reimagine authorship as a collective, dialogic process. Indie filmmakers, positioned at the intersection of tradition and innovation, can embrace their role as mediators—curating human and non-human inputs to forge resonant, disruptive works. In an AI-augmented future, the auteur may be redefined not as a solitary genius but as a facilitator of new discourses, challenging Leviathan’s dream from within.

ALL ARTICLES: